We Need to Stop Talking About AI

Time to close the context window

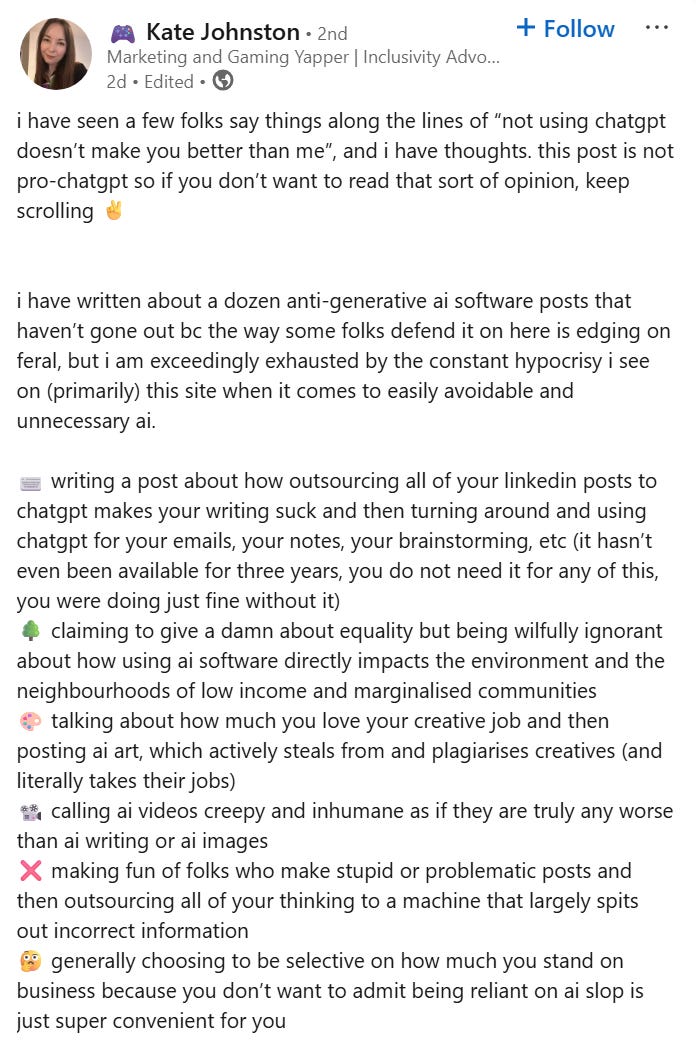

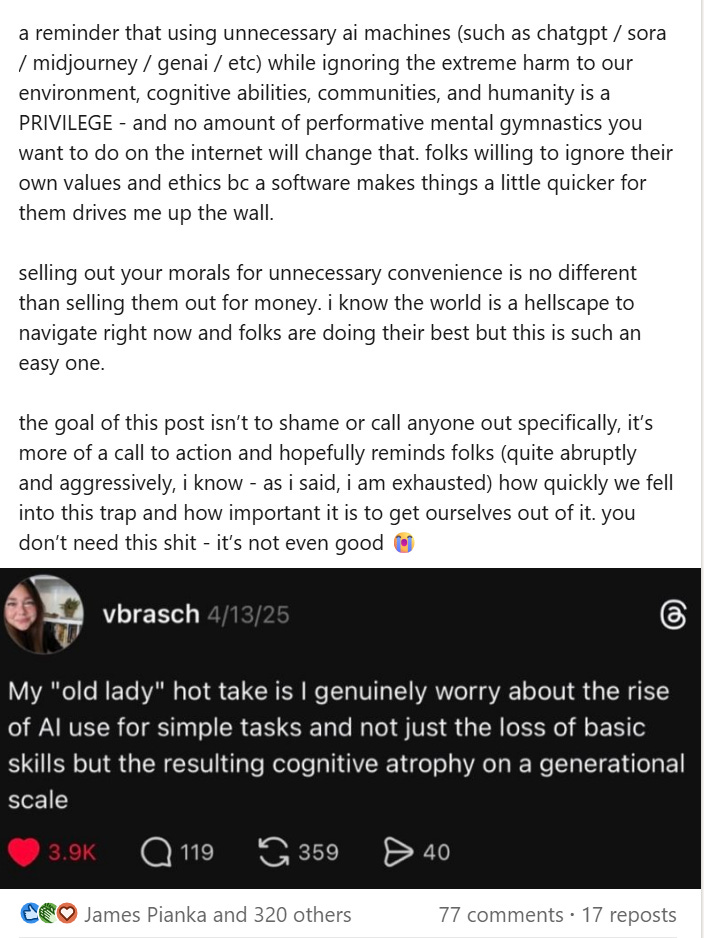

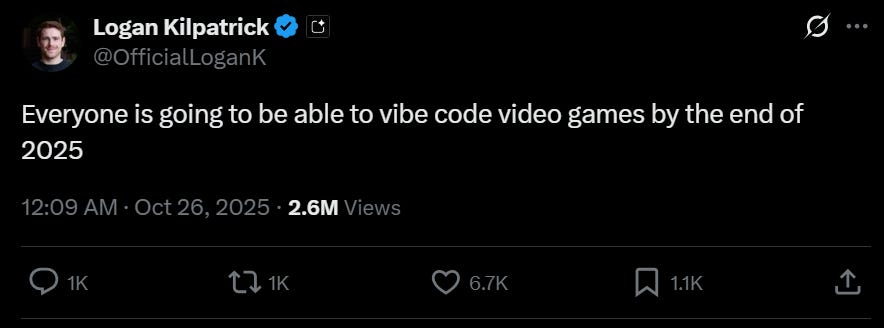

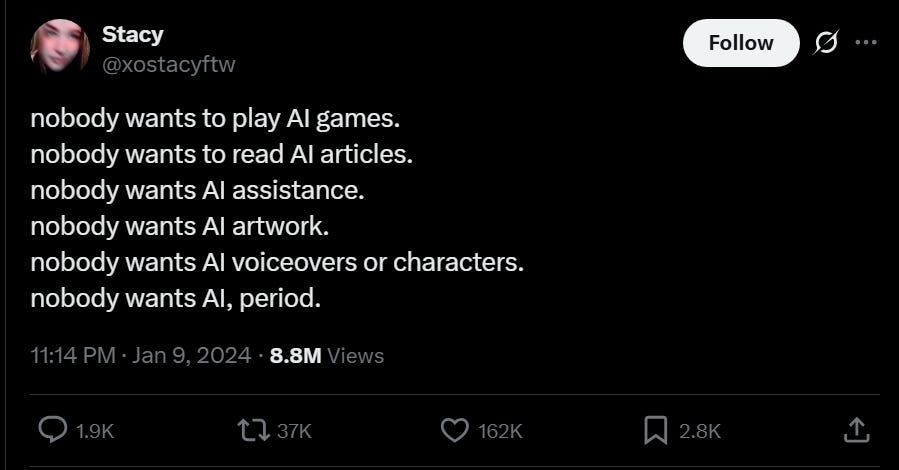

I present, for your consideration, a selection of game development AI-related posts I’ve come across recently:

Either you are “selling out your morals” if you are a game developer who asks ChatGPT to remind you of some syntax, or everyone will be vibe coding games “by the end of the year”. Glad we’ve got that clear.

In his talk opening last year’s AI and Games Conference (which focusses on everything from traditional in-game symbolic AI to machine learning), Dr Tommy Thompson commented that, “The narrative around AI for game development has got away from us” and highlighted some amusing yet slightly concerning abuse he was sent via his speaker submission form:

(As an aside, Tommy’s content is great in general, and he’s been around long before the current gold rush, covering AI in all its permutations.)

AI is obviously polarising - and we’ll discuss that in due course - but we’re also experiencing a form of context compression: every single possible criticism and defence of AI is being elided.

Here are just some of the individual topics that tend to be amalgamated whenever AI is discussed:

The potential appeal of AI content

The efficacy of AI, both now and in the future

AI’s historical and ongoing relationship to copyright and intellectual property

AI deployment within enterprise and its effects on labour

The externalities of AI and their socioeconomic distribution

The valuation and financial dynamics of AI companies

Concerns around “AI psychosis”, “cognitive atrophy” and similar mental health impacts

That really is a lot isn’t it?

AI Affinity

There’s a No True Scotsman-adjacent structure that creeps into discussions around AI’s appeal:

Nobody will like this AI output → Nobody should like this AI output

People will always like Big Macs; the fact that they should probably always eat something else is a distinct issue. If we care about food and the culture around it, then we might try various approaches to convert them to something else: maybe we can make a gourmet burger which tastes better, or we can give them a more personable service experience. But no matter how hard we try, we won’t be able to eradicate all Big Mac enjoyment in the universe.

Almost everyone who practises a craft overrates the global importance of that craft.

This is why people involved with a medium tend to consistently overshoot the audience: children’s TV execs spent decades trying to create compelling programming for young teenagers with increasingly elaborate and costly formats, only to be absolutely stomped into the ground by Minecraft videos via cheap webcams a decade ago. As the walls around content creation come down, we discover that audience tastes are - on average - not as refined as we might have assumed.

In this context then, it’s astonishing to still see statements like “a general audience needs to perceive artistic intent” when a truly general audience is demonstrably incapable of parsing artistic intent: look at the perennial confusion around Starship Troopers.

The final nail in the coffin of this argument should be that AI content consumption is already happening at scale: we don’t even need to speculate about whether or not the technology will improve. Just a singular crass example: the AI-generated Italian brainrot memes attained galactic popularity on social media in early 2025, then popped up again in Steal A Brainrot in May, contributing to the only Roblox game to have surpassed 20 million CCU. These characters are so significant that there is even an ongoing IP dispute over Tung Tung Tung Sahur, who, for my older readers, is a horrifying anthropomorphised wooden drum which carries a baseball bat and probably should get its thyroid checked…

We need to accept that a mass audience relishes - for want of a better word - slop: Mrs Brown’s Boys was voted the best sitcom of the 21st Century; Baby Shark is the most viewed video on YouTube; at one point Kylie Jenner’s baby announcement photo and a picture of an egg were vying for the most likes on Instagram. People will unapologetically enjoy crap and it has never been easier to create it.

I’ve never understood the weird denialism that so many creative people hold around this issue: acknowledging reality doesn’t mean you have to embrace it. In fact, it’s quite the opposite - you can’t truly hate something if you don’t believe it’s a real threat.

So then the pivot happens: ah, but they should be consuming something better. “Should” and “better” are doing an enormous amount of work here: we’re making two distinct aesthetic and moral judgments in the same sentence. Every creator or artist has a variant individual perspective on this: personally I enjoy work that has popular elements to it and which plays with preconceptions; others prefer stuff which is totally inaccessible to a casual audience; others still just want to make anything that will sell.

Presupposing that our values around “should” and “better” are a done deal is the height of self-righteousness: we have to continually and actively demonstrate our opinion through the work we create. Isn’t it better to focus on what we can do rather than on the moral failings of the audience?

Traditional creative methods are never eradicated: they are recontextualised based on their interaction with the prevailing mode. The prevalence of cheap convenience store sushi leads inevitably to Jiro Ono.

To return to my original point, we shouldn’t be parachuting in these extremely complex conversations when we start from a place of determining what we think the audience is going to do in the future.

Code Review

Taste is a very slippery topic, so what about something more grounded?

Games suffer from a real misapprehension by both the general public and other tech sectors: they’re either uniquely opaque and unapproachable or “just software” that can be automated away with a few clever scripts. Entwining art and engineering was always bound to create this problem and we’ll never be free from it - it was probably a mistake in the first place. However, AI has once again exacerbated things.

Rapidly assembled vibe coded games have been popping up on a regular basis for the last couple of years: here’s a recent example.

Naturally, work (or a highly exaggerated tech demo) such as this causes AI bulls to start trumpeting that game devs will become obsolete next month, which according to the laws of discourse physics produces an equal and opposite reaction: AI will never be useful for real game dev.

So how can we evaluate this? Discounting the slew of “prompt a game” startups for the moment, there are definitely some real barriers to AI game coding utility in the context of established industry workflows.

One major issue is context: at the time of writing, LLM’s struggle to understand the very large contextual spaces in which traditional game dev operates. Even a single well-stocked Unity scene can be overwhelming, meaning that AI assistance isn’t going to be nearly as impactful as it might be in other spaces.

So no, you won’t be able to vibe your way to a complex city-builder in Unity next week, despite some early efforts in this sort of direction: you’ll still be copying and pasting into an AI chat window in a process that is vastly slower and more cumbersome than simply learning how to program yourself.

Talking to experienced game devs, they tend to use LLM’s for occasional reminders and looking up documentation rather than plugging Claude Code into their project and just letting it fly. Some are regularly using assistive tools such as CoPilot and getting some mileage there. This is a small impact - but it’s non-zero - and I would be extremely surprised if it doesn’t grow over the next couple of years with this cohort. There’s a real push to make documentation more readily available in LLM-style interfaces - this is a logistics issue and doesn’t require an improvement in the technology in order to leap forward.

Full-blown code generation tools currently are highly prone to spitting out garbage - it’s not particularly worth speculating on the trajectory of this, as they will either improve somewhat or take a dramatic turn for the better as has happened elsewhere with other AI functions. Overall coder sentiment is improving and utilisation is higher, according to this recent Stack Overflow survey.

Let’s remember that many are framing this as an absolute: AI has to be perfectly bad such that we can avoid engaging with it utterly; or it has to immediately replace every junior and mid-level programmer in the industry. Is it so wild to suggest that there might be a middle road?

Just as we found when looking at audience affinity for AI, this entire domain unfolds into intense complexity as soon as you start looking into it, and therefore merits much more than a handwave. Here too, we’ll find a pivot to an ethical frame as soon as any ground is given on efficacy: it might be useful or convenient but it’s innately bad, so that doesn’t matter.

Copyright Complications

Let’s engage more directly with the moral dimension: what about theft on an industrial scale?

Some AI systems still have real issues with producing output that infringes on existing copyright: there are obvious arguments to be made around voice cloning of actors as well as other problematic areas such as image rights, for example. That’s before we even get into training, which is becoming a hot-button topic again at the moment, with its own vast array of considerations.

As I’ve said before, I don’t think we were ready - culturally, socially or legally - for the implications of generative AI in particular. It was rolled out prematurely with the traditionally contemptuous “forgiveness not permission” attitude displayed by so many tech companies and we’re still dealing with the knock-on effects of this today.

But If we accept that there might be some value there, then it follows that we may need to make some long-term cultural adaptations to acknowledge the event of AI. It is possible to make this statement while still being critical of many AI approaches and use cases.

Sampling in music production might be a helpful analogy: sometimes, it’s obviously just culturally deleterious copying, whereas on the other end of the spectrum it’s demonstrably a valid creative discipline stretching back decades.

Nowhere is this more apparent than when it’s taken to extremes, as this project based on sampling tiny fragments of copyrighted works demonstrated way back in 2008, and so definitions become problematic. Even though some of the legal issues are extremely murky, with ridiculous situations like this suit over a single “oh” sample apparently directly contradicting previous case law, we live in a culture where sampling is a broadly accepted practice.

Given all this, I don’t believe that the intellectual property issues around AI are trivial enough to be treated as a quick gotcha when another facet of the argument is failing. They are significant and important - they deserve space to breathe.

Tool Use

IP issues feel very abstract when we could be talking about people’s lives: only the most hard-headed accelerationist would be comfortable with the callous and chaotic deployment of AI in enterprise over the last few years.

Some areas of games have been hit hard by this, with tightening market conditions providing an external incentive to deliver cuts at any cost, and AI falsely appearing to provide a ready solution. Ignorance plays a huge part here: senior leadership implementing AI at speed because they “don’t want to be left behind”, then rank-and-file employees having to wrestle with useless systems and overcomplicated processes is all too common.

Enterprise needs to accept that we are in the Tools Era of AI and that this will likely last for a number of years.

However bullish you might be on AI, it is clearly currently still a framework which needs to be wielded by a human in almost every situation. Only highly specialised systems which have been road-tested to oblivion can produce a near-zero error rate: look at Waymo for example.

If you’re going to utilise AI in your processes in any capacity, it needs time, consideration, testing and humanity. It needs strategic and operational work to apply: if you talk to the more grounded people at major AI companies, they will tell you that between labelling data, managing context and verifying outputs, we are miles away from drag-and-drop AI solutions in many domains. This might not be a worthwhile investment if you’re looking for short-term gains.

The root of these organisational issues - however - extends well beyond AI and into the realm of business as a whole.

Particularly in games, there is still a very poor understanding of the operational dynamics which create great products: the commercial and creative arms have been at odds for decades and there’s no sign of that slowing down. We also struggle with discipline when it comes to creative and production leadership. It seems that many larger companies have forgotten how to allocate capital in the service of actual players rather than imaginary ones - this is why the current “AAA is being embarrassed by indie” narrative is so prevalent.

In summary, this merits a much broader conversation than just “idiot managers tried to use AI” - I don’t think we should be content to use it as a punchline.

Bubble Bobble

Let’s take a look at another pivot

AI has no intrinsic value → AI is overvalued

There is absolutely no doubt that the Pro-AI camp relies on shifting definitions and timeframes aplenty. Valuations also look scary, as do some of the financial practices involved: it all feels frothy.

This is a great video from hyper-deadpan finance YouTuber Patrick Boyle exploring some of the commercial shenanigans in AI currently and doing some gentle interrogation into the possibility of a larger bubble: it does a greater job of delving into all this than I possibly could, as well as touching on environmental impacts.

Yes, even Patrick can’t resist transitioning into another domain here, with water and energy consumption being further cards in the decks of AI critics. At this point I have to tap out - Geography was by far my least favourite subject at school and I don’t think the world is ready for my malformed climate opinions.

The AI Society

Is AI making us stupid, or perhaps worse, delusional? Will it cause an epidemic of mental illness?

We should absolutely be critical of historically poor safeguarding from companies like OpenAI but I can’t be alone in thinking just how crass it is to drag individual incidences of psychological distress into our conversations simply to “prove” to each other that we are perfectly right about the trajectory of technology. In games, we should know better than anyone that emotive systems can have profound positive and negative effects on vulnerable people: these need to be monitored and understood specifically at an appropriate scale.

This video from Eddy Burback covers this issue in a funny and thought-provoking way - it is both indicative of the key dangers around “sycophantic” models and thoroughly damning in terms of how this reflects on large AI companies:

Do I need to say it again? No, I don’t think this is an appropriate “gotcha” for AI; nor do I think it’s suitable to be waved off with “well, this just proves the tech is powerful and it’s up to individual users to deal with it.”

New Chat

We started talking about taste, craft and technical efficacy but then escalated immediately to Very Big Social Questions as we all got increasingly out of our depth. To even engage in this conversation, you now have to be a subject matter expert on everything from global music preferences to macroeconomics to mental health safeguarding: this is unviable.

It’s impossible to have a completely unbounded discussion about anything: if I ask you if you want a cup of tea and you respond by immediately berating me about water usage, then suddenly start ranting about the dangers of stimulants, I’m probably just going to need to drink tea on my own.

When we talk about AI, we’re talking about the potential for genuine harms as well as genuine benefits and promise. But the real issue is that we’re not talking about these things: we’re talking about ourselves.

In this video on a recent Twitch controversy, the psychiatrist Dr K discusses the cultural dynamics of the way divisive events are discussed online - I recommend giving this a watch even if the specific issues being discussed aren’t of interest.

AI has become a lightning rod for everyone’s dreams and insecurities: this is why the discussion has completely lost all proportionality. Job insecurity, intellectual and cultural insecurity, outgroup hatred, financial mania and greed, powerlessness and isolation are all in play across the board. The enemy is the tech bros, or millionaire execs, or woke artists or lazy European socialist degrowthers depending on who you talk to. They deserve no quarter and must be defeated at all costs: the future of humanity depends on it.

We can think that AI output is utter garbage but that some people will still truly enjoy it. We can think that AI code generation will eventually become great but still have concerns about copyright issues and still value the creative input of programmers. We can think that the tech is promising but the water consumption is too high. We can even think that some jobs will potentially be replaced but still care about the impact that transition will have on the wellbeing of individuals.

Except we can’t think these things - not in public at any rate - because they don’t send a strong enough signal to one of the two poles. We’re not able to step outside of these dynamics and think about the culture we’ve created.

We don’t need this level of rhetorical violence to feel secure in the future of creative industries. Given that security, I’d suggest that the most important focus for immediate specific pressure is the misguided deployment of unsuitable AI systems in a manner which harms both productivity and job stability; I would go further and say that, in games, we need to start taking a harder and more comprehensive look at our business models and processes.

While I try to skew optimistic with my posts - as I think there’s more than enough game development pessimism on Bluesky to fill several Texan data centres - I am not at all hopeful that the conversation will shift in the way I have suggested. So many people have become deeply personally invested in waving the pro- or anti- AI flag, and that level of investment leads to pivots, chameleon arguments and siloed personal resentment.

Culturally speaking, we just can’t parse all of this simultaneously.

Thank you! A friend made a great point on IP recently which is that training should simply have been a new category of license and that the AI companies should have been much more transparent and proactive around considering it as such. Maybe things will go in that direction more now as the various lawsuits shake out in different countries.

Labour is a very tough one - personally I think that a huge amount of current AI enterprise deployment which is aimed at instantly replacing jobs is misguided; equally I think there might well be a significant long-term labour impact. In games, like I mentioned, I think we really need to look at business models before we look at AI specifically in terms of sustainable companies that can provide long-term jobs.

Hey, great read as always. Your 'context compression' point is so astute. It feels like everyone's shouting AI and missing the plot. How do you see us better assessing the labour and IP debates?