Developers are indolent snowflake crybabies whose apathy and cynicism results in worthless output.

Gamers are thoughtless seething troglodytes who explode into a frenzy when confronted with the slightest inconvenience.

Pretty tedious to hear those tropes again isn’t it? All of us, irrespective of our role in the games ecosystem, should strive to transcend these stereotypes, no matter how unfair. We should think about how carelessly we brandish them and also about how we can avoid embodying them.

Can we ever make progress there, and is there anything productive to be learned from the most recent flare-up of these ancient conflicts?

Part One - Baldur’s GateGate

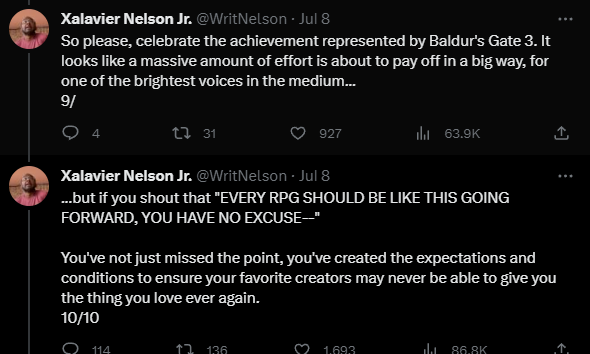

Recently, game developer Xalavier Nelson Jr posted a thread in anticipation of the reaction to the release of Baldur's Gate 3:

I'm not going to re-litigate all of these points - there's been enough of that this week - but I will be looking at the basis of this argument and taking a snapshot of the response to it.

One aspect perhaps worth mentioning is that most developers will have readily available context for the form that "raised standards" (as delineated in this specific context) tend to take, whereas this may not be immediately obvious to players or the media.

To a developer, it is self-evident that by "raised standards" Nelson doesn't mean general improvements in overall game quality.

His words transparently aren't a call for stagnation, an endorsement of laziness, contempt for the audience, a rejection of ambition, a snub to progress, a refusal to learn from success, or an expression of fear and terror at the towering potency of Larian's development power.

He's expressing frustration with a highly specific genre of feedback or criticism, a stance which, ironically, can serve to thwart innovation, progress and risk-taking from devs:

Developers are often discouraged - by both the audience and those who hold the purse strings - from taking risks out of fear that their work may not "live up to expectations". These expectations are often not the true expectations of players, but perceptions that can be formed based on thoughtless comparison or closed-mindedness. They emerge from the aggregate of millions of tweets, reviews, YouTube hot takes and Steam community tirades.

This represents a shared experience for most developers. We worry that our games may not have enough content, that the audience will compare our art style to a game which may have had greater resources and a different technical focus, that we will be review bombed on launch because one of the thousands of decisions we had to make under pressure violated some implicit unreasonable standard we weren't aware of predicated on another game we haven't even played.

We care about these issues because many of us have experienced them multiple times: they are essentially the background radiation of the games industry - the land mines that must be avoided on the way to releasing a successful title.

Ultimately, we worry because we want to make good games that people enjoy, and because we want to be able to make new games in the future.

None of that matters to a subset of our audience though, and you can guess what happened when The Gamers Logged On…

War never changes

The overriding popular narrative around game production is still that developers are cold-hearted money-grubbing cynical individuals devoid of emotion who love nothing more than hoodwinking their audience for cash.

This is base camp for much of the "angry gamer" philosophy, which goes on to make the following inferences: games that fail frequently do so due to a lack of "passion" on behalf of their creators. More passion equals better results - there are no other variables. If a game ships in a bad state, it's because the developers didn't care enough to finish it.

Get good

As I mentioned at the outset, those who haven't been exposed to the full blast of gamer expectations directed at their own work for years were able to infer that the gist of the original discussion was as follows: "That game is really good, and you shouldn't expect games to be that good going forward".

That's a direct quote from YouTuber MoistCr1TiKal (aka Charlie), who characterised the discussion as "calling the wambulance about Baldur's 3 being 'too good'" in response to Destin Legarie's IGN video on the topic.

Why don’t developers want to learn from good games? Why wasn’t that the “first thought” in Nelson’s post? This is an absurd line of questioning, as professional game devs do very little other than learn from successful prior work. It doesn’t needs stating because it’s implicit, especially if you consider the context of who is speaking.

In any case, what does “good” mean?

Larian founder Swen Vincke responded to this whole kerfuffle in an interview with PC Gamer:

"Disco Elysium changed standards on the fly with a small team, right?" said Vincke. "That's a completely different standard now. There are so many games that change standards, to the point that there's no standards, was my thing. But I think you should always strive to evolve, especially in this medium which is different than other media in the sense that technological evolution has always been a big part of it. There's always been innovation, but at the same time, it doesn't require massive technological evolution to do something crazy, and cool, and different than what anybody else has done before."

The real point here is that "standards" become implicit and are deployed unconsciously as they shift over time - as Vincke indicates, they merge into the morass of varying audience assumptions. One concrete example of this is playtime, with expectations there shifting subtly upwards over the last decade, and the tone of audience feedback becoming increasingly hostile towards shorter, more linear games. "Good" is in the eye of the beholder.

Mad as hell

This nebulous discussion of "good" and "standards" opened a window for all sorts of games industry issues to rush in. Destin Legarie's video for IGN was a perfect example of this - I've drawn on that and various secondary commentary around it to collate this list of grievances which are all currently marching under the same raised standard:

Amount of game content

Availability and extent of narrative choices

Graphical fidelity

Optimisation

Quality of writing

Quality of character design

Quality of encounter design

Stability and bugs (eg Jedi Survivor and Cyberpunk 2077)

Re-release pricing for a pay-once game (eg Red Dead Redemption)

Paid DLC in contrast to free DLC in a live service game eg (Destiny 2)

The base pricing of paid DLC in a live service game (eg Diablo 4)

Balance controversies (Diablo 4 again)

Mass Effect Andromeda…just Mass Effect Andromeda

Loot boxes with respect to encouraging gambling

Underwhelming launches in general

Developers apologising for underwhelming launches with white text on a black background

Developers at all other similarly sized studios not making the "effort" to compete with Larion

I'm sure there's more but you get the point. There are obviously some valid concerns here, and as context for the wider state of gaming culture it’s clearly indicative that there are some significant problems, but taken together it’s something of a wall of noise. The discussion rapidly became decoupled from its original basis in a way that reminded some of gaming's cultural nadir in 2014.

Part 2 - Action and Reaction

I don't think anyone is looking for the return of that era, so this might be a good opportunity for everyone to step back from the brink. I'm going to focus on the industry and the audience in turn to suggest a possible route out of hell.

The Industry

I'll begin with the games industry first because, even though I am involved with it, I want to demonstrate that I'm not in the business of writing apologia for its worst tendencies. There are plenty of things that companies and individual developers can focus on without needing to worry about anything that the audience is doing.

Monetisation and Commercial Strategy

Monetisation is a key issue that is driving justified resentment from vocal segments of the gaming population. This animosity is accumulating from the actions of some larger players in the space and being unleashed on smaller developers with a public profile: this is unacceptable, and the companies involved need to take greater responsibility for their models and the way they communicate them to players.

As Charlie described it in his video "The focus has been on nickel and diming consumers, just squeezing all the water out of a towel" - players should not be made to feel that way.

No player should ever be surprised by a monetisation model - they should not be placed in an ecosystem which suddenly hits them with massive unexpected charges; they should not be subject to pernicious 'dark pattern' style UX design; they should not be induced to wildly excessive spending. If you're going to use these models, then you should be fully transparent and open about them. Yes, price complaints will always happen irrespective of pricing efficiency - this is as certain as death and taxes - but those complaints should not be fuelled by your own sleight of hand.

More work needs to be done at the product and platform level on protecting vulnerable adults and children from being exposed to gambling-style mechanics. If this area of the industry doesn't take the opportunity to clean up its act, punitive regulation could well come in which swamps everyone making a game at every level - even those without loot boxes or similar systems. So, stop squeezing the towel and focus on building long-term customer trust, kindness and generosity - that is where the real value lies for you and your shareholders.

Communication

It's been eye-opening to me over the last few years to see just what a huge difference communication with the audience can make on development projects. If you're an indie or a public-facing lead on a larger project, take the high road, keep up the conversation - focus on filtering out deleterious communication, rather than pushing back, however gently. You will be blamed for a whole host of irrelevant issues, sometimes from other games - unfortunately, this will never change so you will need to find coping strategies.

That might seem fatalistic but in practical terms it works best for everyone: gamers who are considerate enough to provide real feedback have their voices heard; devs do not waste their time trying to address unfalsifiable unquantifiable narratives within their communities about how much they "truly care" and other broader cultural noise.

I have seen fairly hostile forums turn from toxic "lazy devs" style cesspits to quite pleasant places to be just employing the following two measures:

Eliminating personal insults and excessively disrespectful communication with consistent moderation

Regular, honest, transparent development updates that explain in detail how community needs are being met within the game

That's it - no rocket science and no change in the "passion" level - just human beings having a conversation.

You need to take the lead on defining the terms of "good" early on in your game's public life. You will never be able to live up to the expectations of all players, so you need to take a strong line on who your work is for and provide those players with a generous experience. Offer something free if you're going to introduce a new paid item; keep rewarding the community who have stuck with you for a long time. "Good" is an impossible standard, but "our players are happy" is much more practical in terms of ambitions.

Courage

Personally, I don't think we need to worry too much about "raised standards", however you define them.

That is not to devalue efforts to communicate about the industry to a mainstream audience - while that can be thankless, and the majority of players unfortunately do not care, it may well have an impact on individual people and how they think about games.

What I am suggesting here is that developers, publishers and funders do more to challenge their own preconceptions around trends and audience expectations.

We need to have courage about our relationship with audience validation and feedback. Too much external influence early on can stifle creativity; too little back-and-forth with players throughout the dev cycle can result in a whole host of unforeseen issues. We have to occupy that difficult space of boldly striking new ground but having the humility to bring the audience along with us.

At the high-end, as I mentioned previously, sometimes riding the next great commercial wave is the wrong move. Strategically, revisiting your "where to play" and "how to win" decisions with a view to uncovering untapped potential from neglected customer segments is something that should be happening regularly in the games industry, not every five years or when there is a dramatic shift in the fortunes of your particular company. It should be an active process.

Ultimately, we need to focus on output. No player is going to care about your optimisation woes, the maturity of your tech stack or how long it takes you to rig a character in comparison to a game from ten years ago - look at the value to the player that older games provided to their contemporary audience and think about how to deliver that again. There is still a lot of uncharted territory in modern gaming that can be mapped by learning from history.

Have the courage to continue caring about your audience, even if it doesn't feel like that is always reciprocated. Every developer knows the immense value and support that the gaming audience can bring, as well as the frustrations of dealing with its more pernicious aspects, so accentuate the positive. The audience isn't the enemy, even if some unhappy people do their best to position themselves in that role.

Structure

At all levels, the industry needs to create development structures that allow for risk-taking creative decisions. It's almost impossible to avoid betting the farm in game development at any scale, but shouldn't stop us looking for ways to improve.

The route forward is to take clear decisions about your projects and your career. Great games are made either by exhaustingly brute forcing your way to the end of development, often resulting in significant human cost, or by a tightly defined scope and production structure: as a developer, you must consciously choose your poison. Go into studio jobs or your own work with eyes open.

Similarly, the structure you employ within a game should help to define its scope.

"Simple structure can carry complex content, complex structure implies simple content - when you're a small developer…you choose one" (Gareth Damian Martin - BAFTA talk on Citizen Sleeper)

I recommend Gareth Damian Martin's recent talk on their development of Citizen Sleeper, which - as they mention here - has certainly stood up in comparison to some big budget RPG titles:

The Audience

Kindness

It's not possible to reason someone into empathy, but kindness to other people is practical even if you're not quite feeling it at the time. When gamers or content creators rail against "the industry", particularly when they unleash their opinions on individual developers online, they can often forget they're speaking to another human being. Just as the industry needs to respect individuals and should rightly be called out when it fails to do so, so too should the audience: we can all improve this together. If you're frustrated by the myopic market-obsessed excess of modern society, you can absolutely be certain that the overwhelming majority of game developers feel just the same way.

Gamers are kind people. The massive amount of support and love that devs experience in person at live shows and conferences (I'll never forget my first PAX when people had heard of our game for the first time!), the thoughtful messages players will send about how a game affected them, the way that players can champion small indie games and create staggering hits just by their own word-of-mouth, the friendly, giving, open nature of many communities…there is an endless list of examples I could give. This is what real gaming as a hobby (if you want to call it that) is about and it shouldn't be contaminated by divisive hateful elements. Keep fighting for that.

Curiosity

It's pretty depressing to see some of the ultra reductive views on game development that have permeated enthusiast circles for decades get trotted out once again. Naturally, a lot of this is an understandable defense mechanism against absorbing an enormous amount of context, but competent adults in 2023 should not be brandishing opinions like "games only fail because developers are lazy" or "any team could make Elden Ring if they just cared enough" in public - it's embarrassing and it fosters unnecessary resentment.

A key issue here is just a lack of curiosity. The overwhelming majority of devs in the world would love nothing more than to work on a lavishly funded, tightly scoped, richly textured passion project that gamers love, sold under a clear, mutually agreed commercial model with flexible deadlines, extensive community support and ongoing revenue that supports indefinite updates in a sustainable manner. That's what they got into the industry to do in the first place - nobody is stamping their feet saying "we can't do it, we won't do it". Nobody is "refusing to learn".

So given that information, why might a game developer suggest that unfair audience standards are challenging for them? What do they really mean by that? Hint: it's not "I'm scared when another developer makes something good".

If you don't like bigger titles and the direction of the industry, play smaller ones. There are now more games released than ever before, for every niche imaginable. Just because the next massive AAA release won't meet your requirements, consider compromising on visuals and choosing an indie title instead - be curious, break away from the marketing cycles of the big companies and seek them out yourself. Games are about gameplay at the end of the day and there's plenty of it out there for you.

Clarity

The games industry lives or dies on the preferences of its players but one problem is that it often receives mixed messages. Some of this is naturally due to a false concatenation of differing voices (which is something to be solved on the industry side in terms of how it filters information) but the audience is certainly able to take action on this as well.

I mentioned the incredible katamari of grievances raised during this discussion above - the net result of all that is attempting to address anything feels like trying to punch a ghost - nobody knows what anyone else is talking about any more.

One way to cut through this is to focus on giving specific, actionable feedback to developers and publishers whose games you love. Gamers are fantastic because they are often willing to really get in there and wrestle with a problem - I cannot express how grateful I am to people who have helped out on projects I've worked on by reporting bugs, suggesting relevant practical features and providing gameplay feedback. There wouldn't be a functional games industry at all without such people - they are often some of the happiest and most involved players.

This can be you! Find developers who do listen and give them specific, actionable feedback via the channels they've set up for that - you'll really be making a difference.

One thing perhaps to realise is that the industry often receives signals from the audience in the form of paradoxes - again, these may sometimes be different groups speaking but the information arrives as if from a unified voice. Here are some current examples:

Gamers often demand that games structured for pay-once "should be free", but all the viable free-to-play models are innately unethical regardless of content

Early Access is often called a scam to sell unfinished games, but Early Access is also how you truly "listen to the fans" - devs are alternately praised and condemned for using it at all

Releasing unpolished games is lazy but delaying games to polish them means you're stringing the community along and producing vapourware

DLC represents greed but games need to be updated indefinitely, even after their initial launch revenue has tailed off

Establishing a framework for DLC from the outset is cynical, but being slow to produce DLC is lazy

Microtransactions are overpriced rip-offs but players as a whole continually spend vastly more money on them than they do on pay-once games

High quality indie games that fail commercially aren't "marketed enough" but advertising is evil

RPG mechanics and grinding are cynical additions but every game is "too short"

This is why specificity matters and hyperbole can be harmful. "I am this type of player and I hate this decision for this specific reason" is much more useful than "Early Access is bad and dumb".

One way of being clear with the industry is to vote with your time and your wallet. If you don't enjoy a game, stop playing it. If you think a cosmetic microtransaction is too expensive, don't buy it. Don't play, don't pay.

Call the wambulance and order me a large French Cries, I'm done

I really hesitated to write this - as I'm coming up to nearly 20 years in the games industry wearing various hats, I've seen this stuff play out so many times before. Opening the door to communication in any form often just results in abuse, death threats, the usual screaming of desperately unhappy people getting mad online about something you personally had nothing to do with.

I have to admit that I am broadly pessimistic about the global outcomes here - I don't think the industry will make all of the changes I've suggested, and some portions of the audience will never alter their behaviour towards developers. When I saw Nelson start down that road, I definitely had a sinking feeling in terms of the response - "have reasonable expectations" is not usually a rational ask of people who currently are in possession of unreasonable expectations. There is a chance this whole debacle just fuels the fire.

Part of me still believes though that the act of discussing these issues is valuable, even if it only affects a very tiny number of people in a positive way. I really hope that's the case, and that this doesn't spiral into another polarised disaster zone - we owe it to ourselves to avoid that.

Ngā mihi nui (thank you) for this! I’m a thoughtless troglodyte but even I avoid ‘gamer’ discourse whenever possible. It’s always nice to read a nice little balanced piece and come away feeling a bit more positive about things. Cheers!